writing for tubax

The Eb Contrabass Tubax is a transposing instrument, written in treble clef like a saxophone. Written pitch is two octaves + a major 6th higher than sounding. The lowest note of the sounding range is Db an octave below the bass clef, and like a saxophone, the standard register extends upwards for two and a half octaves from the lowest note. NB: the tubax does not extend to a low written A (concert C) like a baritone saxophone.

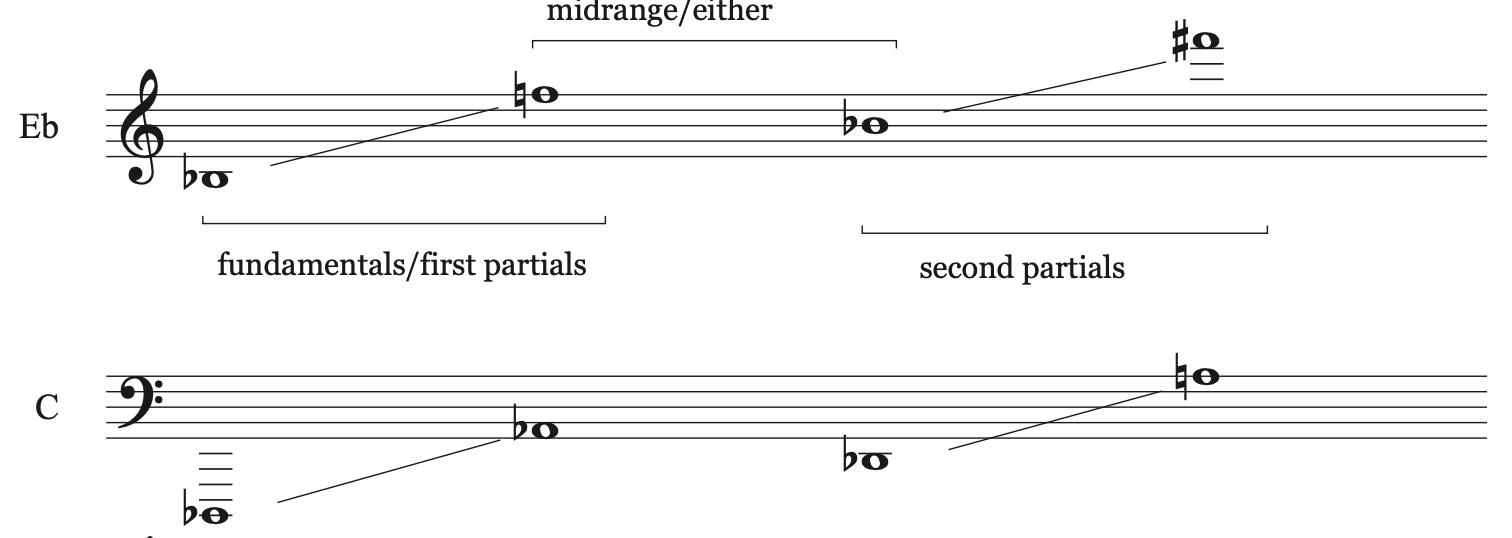

Like all saxophones, the standard register includes notes sounding as fundamentals/first partials as well as notes sounding as second partials (one octave higher than the first). In the middle is a midrange in which pitches can be produced either as a first or a second partial.

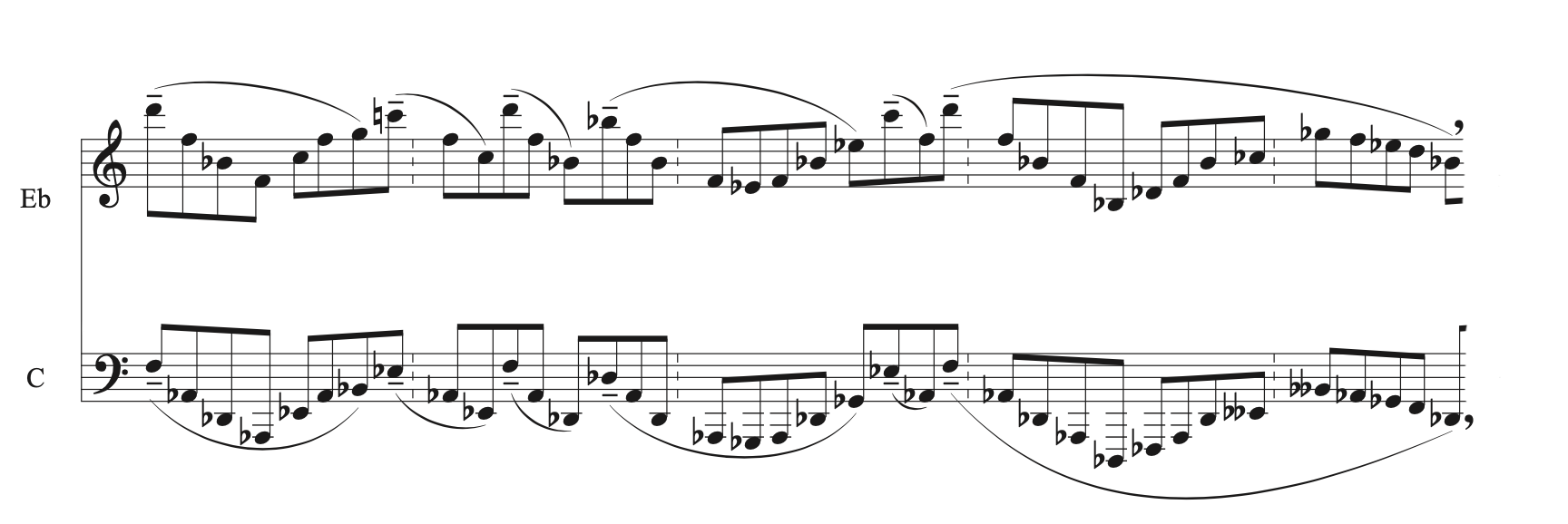

Like a saxophone, the tubax, has a smooth facility in moving between registers as demonstrated in this example from the Toccata movement of my own work Hymn (2021/22) for solo tubax or bass clarinet:

Owing to the lowness of the fundamental register, the functional range of the tubax extends to over five octaves, including an altissimo register of second/third partials and a harmonic/squeal register of upper partials.

A bit of the upper altissimo and squeal register appears in concert with the fundamental register here in the Reel movement:

The squeal register is used more prominently in the Music Box movement from Hymn (for ease of reading in the tubax part I use the small circle/harmonic symbol to indicate a note sounding two octaves higher than notated).

When it comes to multiphonics, tubaxes behave more like low clarinets than saxophones. Most saxophone multiphonics are split multiphonics (also called fingered multiphonics), where overtones of two or more different fundamental fingerings are being sounded simultaneously (which makes them often dissonant). These are, according to tubax inventor the late Benedikt Eppelsheim, “impossible” to produce on the tubax because “it’s too in tune” (I am not sure if this is entirely accurate but I have not been able to produce them yet).

Because the ratio of its bore to its lenght is more cylindrical than a true saxophone, the tubax most readily produces spectral multiphonics. In the simplest sense, a spectral multiphonic is produced when notes drawn from one overtone series are sounded simultaneously.

Here you can see the first 32 nodes of the overtone series built on a low concert Db, which is the lowest sounding note on the Eb tubax. Large numbers indicate the number of partial (first partial is the fundamental); small numbers followed by “c” indicate sharpness or flatness in cents from equal temperament.

When a spectral multiphonic is produced on the tubax, all of the notes of the overtone series based on the fundamental being fingered, upwards of the 32nd partial, are in some sense audible. Because each pitch that appears in the overtone series is repeated in subsequent octaves, and more pitches are added with each octave, the notes that appear earliest in the series occur more often and sound more prominent in the resulting spectral multiphonic. (note for instance in the earlier example that partials 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 are all Db’s, 3, 6, 12, 24 are all Ab’s, and 5, 10, 20 are all F’s, and more new notes are added in between with each added octave). The reinforcing of octaves of early partials across the height of the spectral multiphonic results in the pitches represented by those partials sounding to the fore. Representing chord tones 1/3/5 , these pitches can make the spectral multiphonic sound relatively clearly as major chord.

Approximation of actual, partials 1-32 of a low Db, not all are shown in the treble clef and cents sharp or flat are left out but you get the point. This is the spectral multiphonic that appears at the end of the Bach Prelude:

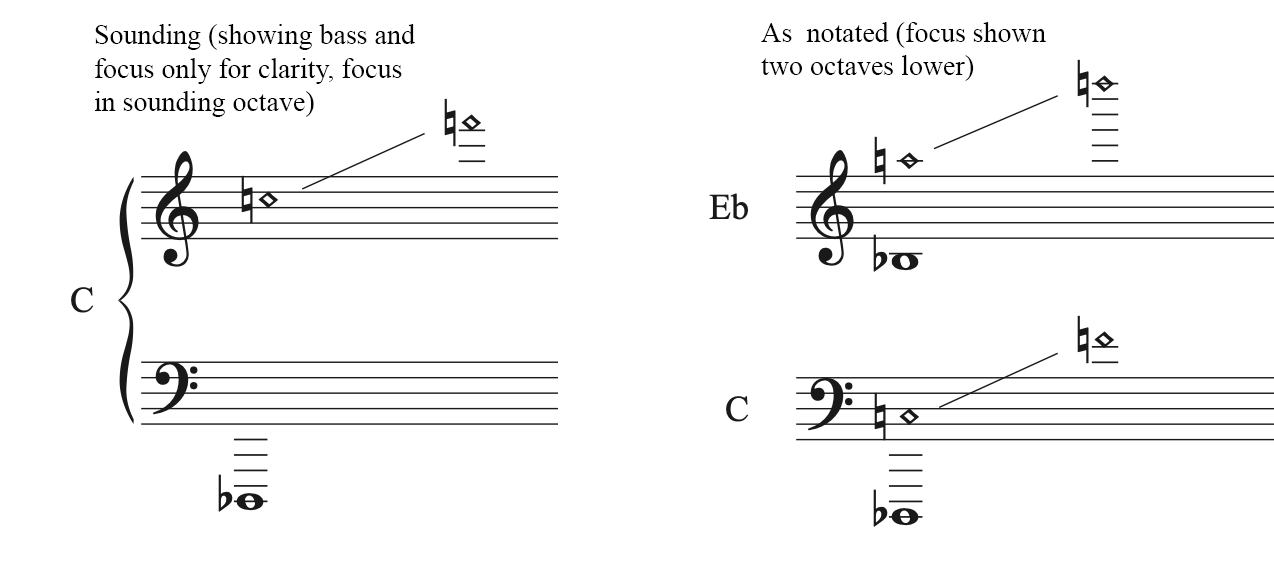

In a spectral multiphonic, two notes are generally more audible than the others: a note on the higher end of the spectrum, which I call the focal node or focus, and a note on the lower end of the spectrum which I call the bass, which is generally the fundamental or first partial. My system of notation relies on a shorthand showing these two most prominent notes: the bass note and the focus note. The bass note is notated using a normal notehead, and the focus note is notated using a diamond-shaped notehead. For ease of reading, and since the audibility of the focus note in a spectral multiphonic begins around the 20th partial, I notate the focus note two octaves lower than sounding in relation to the fundamental.

The range of focal nodes that can be produced with stability is only about an octave and a half at the topmost end of the tubax range. Within this octave and a half, there is a wide flexibility in choosing a pitch. Owing to the closeness of the partials and the nature of the instrument’s saxophonesque construction, both a stable straight tone or slidy gliss between pitches can be easily controlled.

Selecting a focal node that is aligned with one of the most prominently represented chord tones in the overtone spectrum (1/3/5, and 7) can create a very clearly sounding major chord of the fundamental, and when combined with moving fundamentals, traditional counterpoint can be acheived as in the opening of Hymn:

Despite the reinforcement of lower octaves, and given the prominence of the focal node in the spectral multiphonic, changing focus to a pitch outside of the chord can give a different character that makes it sound as a minor chord, or something completely different. In the next example from Hymn, a melody using focal nodes is played over a single fundamental.

It is also possible to move crisply between chord tones as at the end of the piece:

Multiphonics can be added as accents or a timbre change on notes of shorter duration as well, alternating with monophonic notes quickly in real time as demonstrated in my Throttle movement: